5.27 The Surrey Self-Harm Protocol

Contents

- 1. Introduction(Jump to)

- 2. Understanding Self-Harm(Jump to)

- 3. Having a conversation with a child about self-harm(Jump to)

- 4. When a child presents to a non-health professional(Jump to)

- 5. When a child presents to a health or social care professional(Jump to)

- 6. Information sharing and consent(Jump to)

- 7. Safety Planning(Jump to)

- 8. Impact on professionals(Jump to)

- 9. Online safety(Jump to)

- 10. Appendix A(Jump to)

- 11. Appendix B(Jump to)

- 12. Appendix C(Jump to)

1. Introduction

The Surrey Self-Harm protocol is for anyone who works directly with and/or supports children and young people in Surrey. This includes but is not limited to:

- Healthcare professionals

- Social care professionals

- Staff in education settings

- Third sector organisations

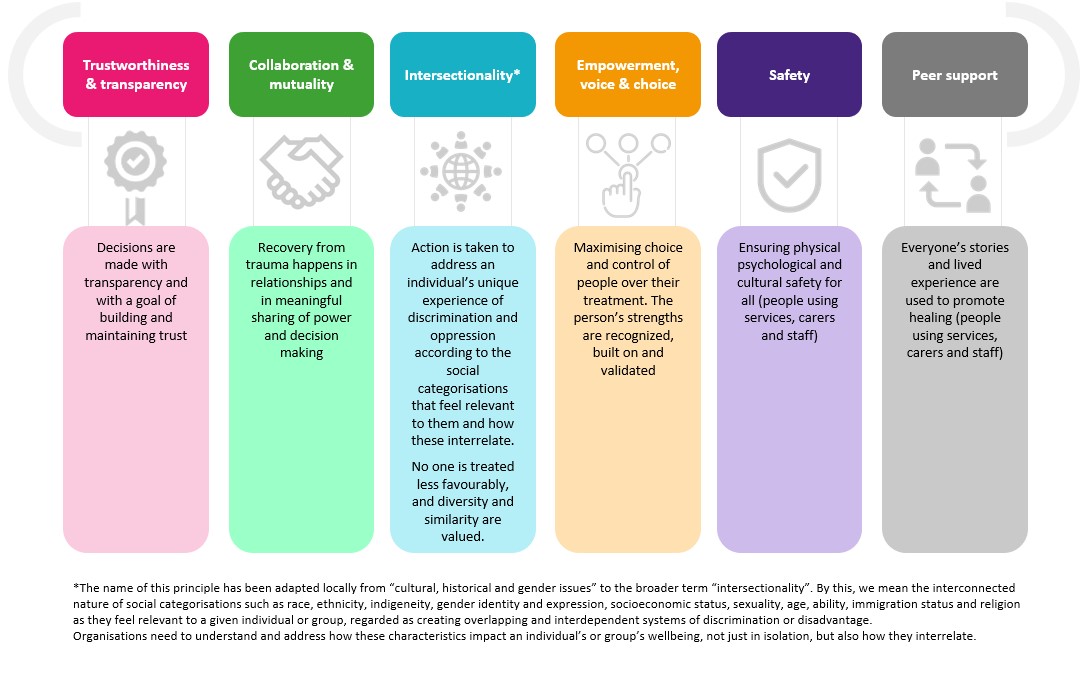

The protocol has been developed with key stakeholders from across the Surrey system and builds on our system Time for Kids principles. The protocol utilises a Surrey Healthy Schools and trauma informed approach, aligns with the THRIVE Framework, and is intended to aide professionals in preventing self-harm and in supporting children and young people who have experienced self-harm appropriately.

Self-harm can take many different forms and varies considerably between individuals which makes it hard to define. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) define self-harm as ‘an intentional act of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the motivation or apparent purpose of the act, and is an expression of emotional distress.’

Self-harm can take many different forms and varies considerably between individuals which makes it hard to define. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) define self-harm as ‘an intentional act of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the motivation or apparent purpose of the act, and is an expression of emotional distress.’

In this protocol, a child is defined as anyone who has not yet reached their 18th birthday. ‘Children’ therefore means ‘children and young people’ throughout. Where we refer to ‘professionals’ or ‘practitioners’ this includes everyone working with children in Surrey.

Although the majority of the information included in this protocol is relevant for early years age children, the focus is on school age young people. For information on supporting the social and emotional wellbeing of children in early years settings please use this pack developed by the Early Years Educational Effectiveness Team.

This protocol does not cover self-injurious behaviours which is sometimes present in the context of Learning Disability or Autism. For helpful information and details of local support services for children with additional needs and their families, visit the Surrey Local Offer webpage.

2. Understanding Self-Harm

Why do people self-harm?

People self-harm for a number of reasons, and it can serve a variety of functions, for example:

- To distract from difficult feelings and emotional pain

- To relieve tension, frustration or anger

- To express emotions such as hurt, shame or fear

- To feel in control of feelings or situations

- To feel something (anything)

- To communicate needs

- To feel grounded back to the present moment

- To create a sense of numbness

- To self-punish, punish others, or avoid hurting others

- To see if it helps (especially if there are others around who are self-harming)

It is important to note that young people are not always aware of the reasons behind their self-harm.

Who self-harms and what increases the risk?

Self-harm is something that can affect anyone. There is no such thing as a typical child who self-harms. However, there are factors that contribute to the risk of self-harm. These include:

- Adversity due to socio-economic disadvantage

- Social isolation

- Adverse life events, for example abuse, domestic abuse, bullying, relationship difficulties, exclusion from school

- Feeling unaccepted/rejected by peers/family/society

- Caring responsibilities

- Bereavement, especially by suicide

- Mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety or disordered eating

- Chronic physical health problems

- Alcohol and/or drug misuse

- Involvement with the criminal justice system

- Neurodiversity – diagnosed or undiagnosed

- Presence of Special Educational Needs and Disabilities

- Identity questions relating to gender and/or sexuality

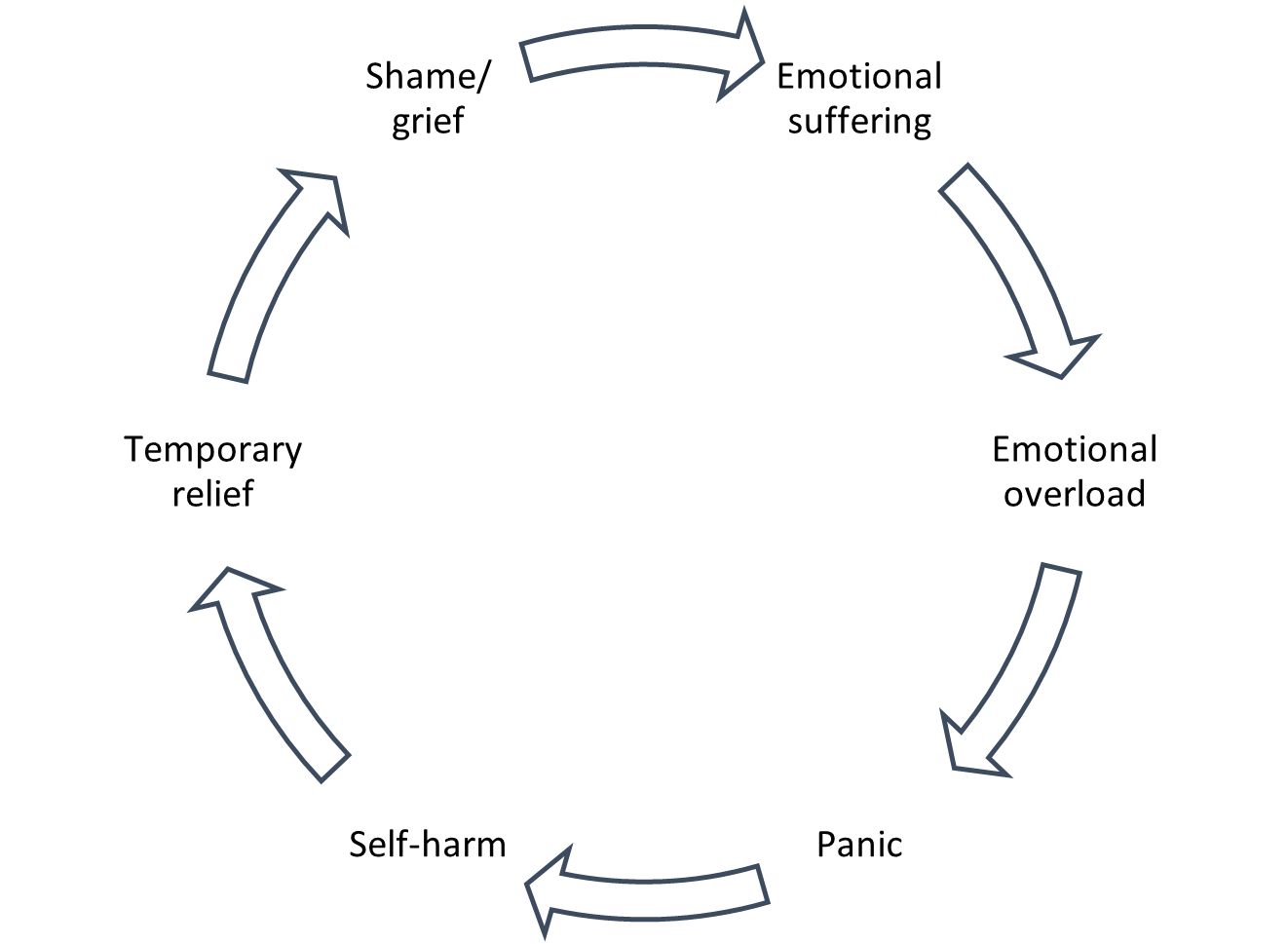

The Cycle of Self-Harm

Although the self-harm may temporarily help a young person to feel better e.g. by numbing emotional pain, the underlying unmet needs will remain. Feelings of guilt, embarrassment and shame can follow, which can increase the likelihood of self-harming again.

Figure 2: The Cycle of Self-Harm, Mental Health Foundation

Warning signs of self-harm

There are a number of signs that may indicate that a child is self-harming. These include:

- Physical injuries:

- You observe on more than one occasion

- Appear too neat or ordered to be accidental

- Do not appear consistent with how the young person says they were sustained

- Secrecy or disappearing at times of high emotion

- Long or baggy clothing covering arms or legs even in warm weather

- Increasing isolation or unwillingness to engage

- Avoiding changing in front of others (may avoid PE, shopping, sleepovers)

- Absence or lateness

- General low mood or irritability

- Negative self-talk – feeling worthless, hopeless or aimless

See also: no-harm-done-professionals-pack.pdf (youngminds.org.uk)

The link between self-harm and suicide

The most significant difference between suicide and self-harm is the intent; self-harm is virtually always used to feel better rather than to end one’s life. However, self-harm with or without suicidal intent is a risk factor for suicide, and establishing intent can be challenging, even for the individual. All acts of self-harm should be responded to with compassion, curiosity and care.

For more information visit:

How Are Self-Injury and Suicide Related? - Child Mind Institute

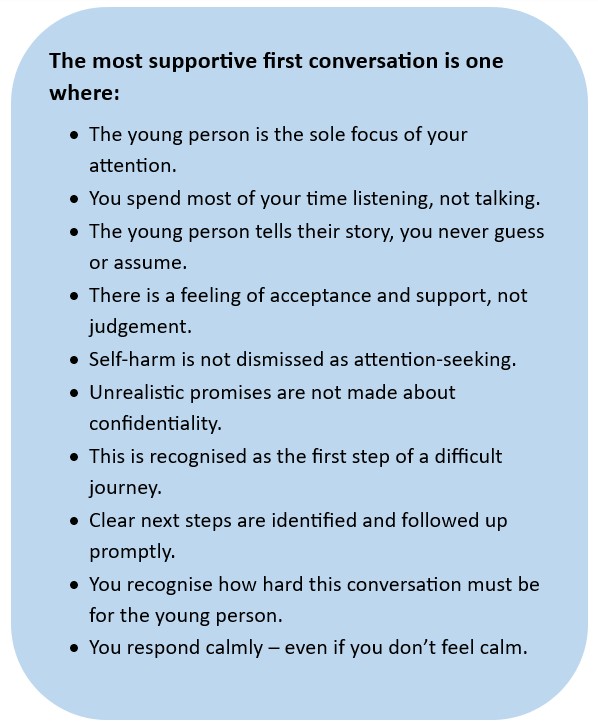

3. Having a conversation with a child about self-harm

Starting a conversation with a young person about self-harm may not be easy, but the sooner a conversation takes place and a disclosure is made, the sooner they can start to receive support for their emotional wellbeing and mental health. The Young Minds website has a helpful page on how to start a conversation, picking a safe space, what to do when a young person isn’t ready to talk and what to do next.

Remember, an underlying problem often causes self-harm; focus on what’s causing their feelings rather than on the self-harm itself. Different things will work for different people, and what helps will usually depend on the feelings the child is trying to manage.

"My biggest help was when someone actually sat down and went ‘screw everything that every other service has said about you, what’s happened? What’s gone on?”

Young Person, Surrey

YouTube - What was self-harm to you? – a young person’s experience’ – produced by Surrey Youth Focus.

This exert was taken from Surrey Youth Focus’ Coffee and Chat session on Self-Harm.

4. When a child presents to a non-health professional

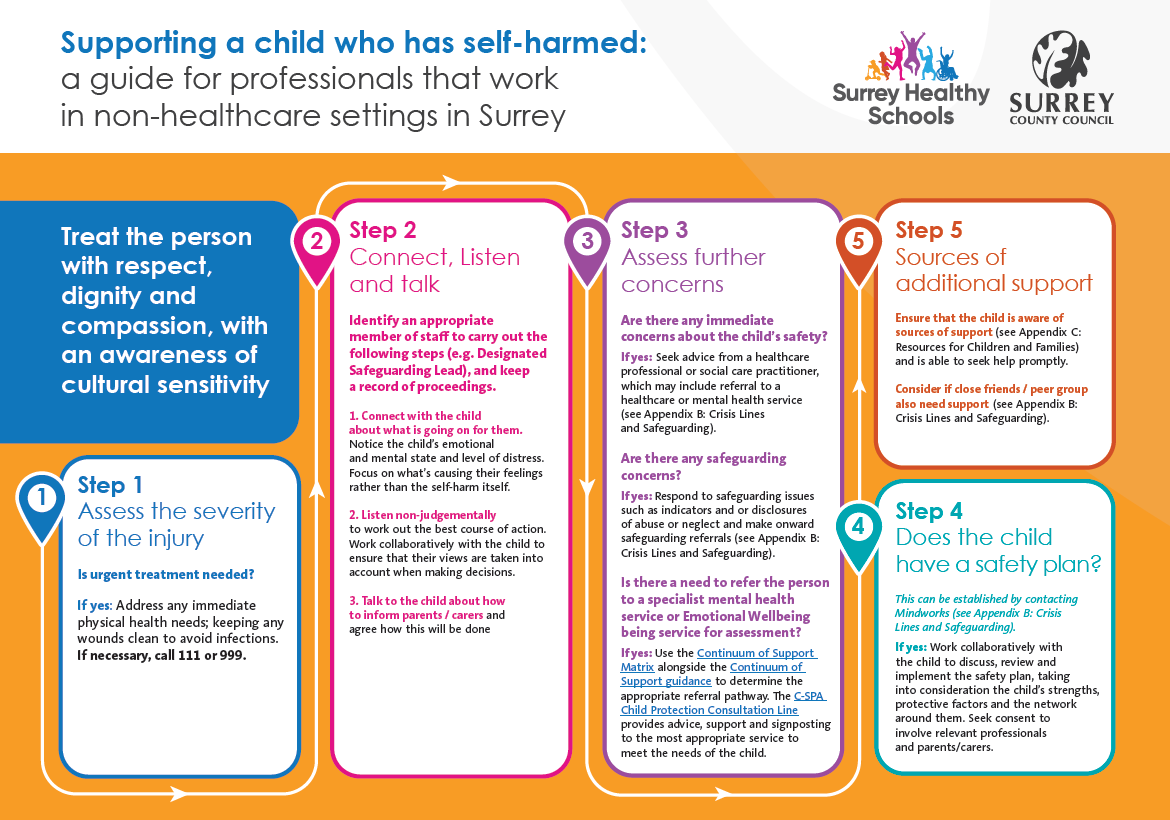

In line with the NICE Guidance on Self-harm assessment, management and preventing recurrence, when a child who has self-harmed presents to a non-health professional, for example, a teacher or a member of staff in the criminal justice system, the non-health professional follow the flowchart in Appendix A: Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for professionals who work in non-healthcare settings in Surrey.

Good practice for educational settings

Educational settings should have a self-harm policy for staff to support children who self-harm. This should include:

- How to identify self-harm behaviours (see Understanding self-harm)

- How to support students who self-harm (see Appendix A: Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for professionals who work in non-healthcare settings in Surrey)

- A commitment to working collaboratively with children to implement safety plans that have been developed in Emergency Departments or other settings (see Safety Planning).

The designated lead should ensure:

- The self-harm policy is implemented, regularly reviewed and kept up to date

- That all staff understand the policy, and are supported with any uncertainties on how to implement it

Remember, no single person is responsible for preventing self-harm; everyone in the school community can have a positive impact on children’s wellbeing.

Addressing self-harm in the curriculum

The school’s response to self-harm should be developed using the Surrey Healthy Schools Self-Evaluation Tool. This helps both schools and services to work together in holistic way to provide a supportive and proactive approach to prevention and safeguarding.

The best way to build knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that help to prevent self-harm into the curriculum is to address the underlying issues through a whole-school approach to mental health.

- Tackle issues ‘upstream’: for example by supporting transitions, promoting positive relationships, helping children who are bereaved, signposting and facilitating access to specialist mental health support, and addressing bullying.

- Use a strength-based approach: focus on building protective factors e.g. social-emotional skills, problem-solving abilities, and a supportive and compassionate school community.

NB: Programmes focused directly on raising student awareness of self-harm and suicide may appear desirable but there is a risk of increasing self-harming behaviour among young people through normalising it. It is recommended that universal approaches to self-harm and suicide prevention remain grounded within mental health promotion activities. See Suicide intervention in schools - Headspace.org.uk

Free Surrey Healthy Schools Approach training and cluster support is available to all Surrey Primary, Secondary and Special schools.

The PSHE Association guidance Teaching about mental health and emotional wellbeing has further information around teaching mental health safely and effectively.

Good practice for third sector organisations

Staff who work in third sector organisations should follow the flowchart in Appendix A: Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for professionals who work in non-healthcare settings in Surrey. All staff working with children should:

- Treat children with respect, dignity and compassion with awareness of cultural sensitivity.

- Be able to identify self-harm and be aware of how to support and signpost to appropriate services.

- Have an understanding of the Surrey Self-Harm Protocol and follow the guidance outlined.

Good practice for criminal justice / secure settings

Staff in criminal justice / secure settings should:

- Treat children with respect, dignity and compassion with awareness of cultural sensitivity.

- Be able to identify self-harm and be aware of how to support and signpost to appropriate services.

- Have an understanding of the Surrey Self-Harm Protocol and follow the guidance outlined.

- Be aware that those in their care are more vulnerable to experiencing self-harm and suicide

- Ensure children who have self-harmed have a safe location to await assessment or treatment following an episode of self-. Consider the appropriate people to wait with the child; it is often not appropriate for uniformed officers to wait with individuals, and parents/carers are not always the best option for the child.

- Be aware of arrangements for:

- Transferring children to healthcare settings where necessary

- In-reach or on-site support

- Information sharing responsibilities – see Information sharing

- How to access health services – see

- Be aware of services available to support their own wellbeing, see Impact on professionals

5. When a child presents to a health or social care professional

Health and social care professionals have a powerful role in promoting positive mental health in all their interactions. They should do this by encouraging good sleep, exercise and eating habits, and the importance of play, family, friends, and engagement with education.

Where a child requires health or social care support in relation to self-harm, practice should be as follows, in line with the NICE Guidance on Self-harm assessment, management and preventing recurrence.

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for all health and social care professionals in Surrey

|

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for all health and social care professionals in Surrey |

|

|

Establish the following as soon as possible: |

Remember to: |

|

· What is the severity of the injury? Is urgent medical treatment needed? (For immediate first aid for self-poisoning, see the BNF's guidance on poisoning, emergency treatment, TOXBASE and the National Poisons Information Service.) · What is the child’s emotional and mental state, and level of distress? Ask directly about self-harm and suicide, including thoughts, actions and plans. Is a referral to a specialist mental health service for assessment needed? · Are there any immediate concerns about the child’s ? · Are there any safeguarding concerns? · Does the child have a care [1]? · The appropriate observation level [2]? |

· Treat the child with respect, dignity, compassion, and an awareness of cultural sensitivity. · Carry out physical healthcare and the psychosocial assessment as soon as possible. · Establish the means of self-harm and, if accessible and safe to do so, discuss removing this with therapeutic collaboration or negotiation (i.e.; large pieces of glass or blades in a wound should remain in place until appropriate medical help is available to assess, burns should be treated by a professional, ligatures removed if possible, medication removed and packets saved to inform health staff, lighters, solvents, or aerosols removed. This is not an exhaustive list). · Assess capacity, competence, consent or duty of care, and seek advice from a senior colleague if necessary; be aware and accept that the child may have a different view and this needs to be taken into account. · Seek consent to liaise with those involved in the child's care (including family/carers and school setting) to gather information to understand the context of and reasons for the self-harm. · Focus on the child’s needs and how to support their immediate and long-term psychological and physical safety. |

|

Discuss with the child and family / carers: |

|

|

· Does the child have a safety plan? · Does the child have coping strategies? · What are the child’s protective factors? Do they have a support network? · The value of sharing information with school, and ways this can be done (see Information sharing and consent) |

|

[1] The plan of treatment or healthcare to be provided to the service user, typically documenting service user needs and safety considerations, interventions to support recovery, and key professionals and practitioners.

[2] A therapeutic intervention most commonly used in hospital settings, which allows staff to monitor and assess the mental and physical health of people who might harm themselves and/or others.

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: specific guidance for Primary Care

|

Specific guidance for Primary |

|

|

· Work with the child to understand what is going on for them: recognise factors impacting their emotional and mental state and level of distress. Explore what’s causing their feelings and why they are self-harming. · Assess the child’s needs, vulnerabilities and safety: include factors such as the severity and frequency of self-harm, the presence of suicidal ideation or intent, any underlying mental health conditions, family dynamics, and environmental stressors. · Engage the family: communicate openly and sensitively with parents/carers about their concerns while ensuring confidentiality and respecting cultural sensitivities. · Provide education: include information about self-harm, its causes, and available treatments. This can help reduce stigma and support families to take an active role in their child’s care. Educate parents/carers on how to recognise signs and where to find further information and support (Appendix C: Resources for Children and Families). · Develop a safety plan: In collaboration with families, develop a safety plan that outlines steps to prevent future incidents of self-harm (see Safety Planning). This may include identifying triggers, creating a safe environment at home, establishing emergency contacts, teaching coping skills, and encouraging regular follow-up appointments for ongoing support and monitoring. Ensure the child’s views are taken into account and consider the child’s strengths, protective factors and network around them. · Collaborate with other professionals: Effective collaboration between primary care providers, mental health specialists, social services, schools and other relevant professionals can help ensure comprehensive care for children experiencing self-harm concerns within their families (see Information sharing and consent). · Share Crisis support with the child and family: see Appendix C: Resources for Children and Families) |

|

|

Make referral to specialist mental health a priority : |

If there is a safeguarding concern: |

|

· The child’s levels of concern or distress are rising, high or sustained. · The frequency or degree of self-harm is increasing. · The person providing assessment in primary care is concerned. · The child or family asks for further support from mental health services. · Levels of distress in family members are rising, high or sustained, despite appropriate support being offered. NB: Calling C-SPA / Mindworks (see Appendix B: Crisis lines and safeguarding) is always advocated if risk is higher with associated concern. Call handlers will then advise whether a follow up written referral in is indicated or another course of action is required. |

Refer to both C-SPA and Mindworks (see Appendix B: Crisis lines and safeguarding)

|

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: specific guidance for Ambulance Staff and Paramedics

|

Specific guidance for Ambulance Staff and Paramedics |

|

|

When a child who has self-harmed but does not need urgent physical care: |

|

|

· Follow the child's care plan* and safety plan if available. · Seek advice from mental health professionals, where necessary (see Appendix B: Crisis lines and safeguarding). · Assess immediate safety concerns, and availability and accessibility of alternative services when deciding whether the child can receive treatment from an appropriate alternative service |

|

|

Record relevant information about: |

Discuss with the child and family: |

|

· Home environment · Social and family support network · History leading to self-harm · Initial emotional state and level of distress · Any medicines found at their home Pass this information to staff if the child is conveyed, or share it with other relevant people involved in the child's ongoing care if the child is not being conveyed. |

· The best way that the ambulance service can help them. · If it is possible for the person to be assessed by or receive treatment from specialist mental health services or their GP. |

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: specific guidance for Psychiatric Liaison Nurses and Crisis Intervention Service

|

Specific guidance for Psychiatric Liaison Nurses and Crisis Intervention Service |

||

|

Step 1: Explore |

Step 2: Record |

Step 3: Share |

|

Work with the child to understand what is going on for them: recognise factors impacting their emotional and mental state and level of distress. Explore what’s causing their feelings and why they are self-harming.

|

Develop a safety plan: work collaboratively with the child and their family to outline steps to prevent future incidents of self-harm (see Safety Planning). This may include identifying triggers, creating a safe environment at home and establishing emergency contacts. Ensure the child’s views are taken into account and consider the child’s strengths, protective factors and network around them.

|

Discuss what information can be shared with school: explain the value of sharing information with school to the child; schools are better able to support children if they are informed about what helps them. Give the child ownership over what is shared unless significant risk is identified (see ).

Share agreed information with the School Designated Safeguarding Lead (DSL) using the DSL secure email database. |

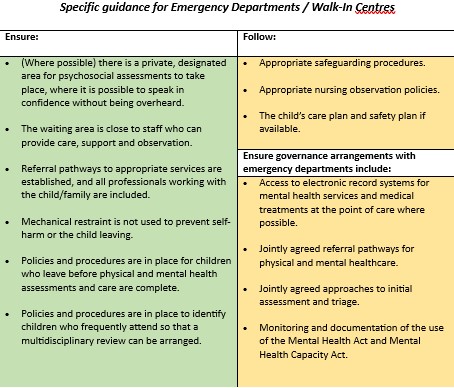

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: specific guidance for Emergency Departments / Walk-In Centres

|

Specific guidance for Emergency Departments / Walk-In Centres |

|

|

Ensure: |

Follow: |

|

· (Where possible) there is a private, designated area for psychosocial assessments to take place, where it is possible to speak in confidence without being overheard. · The waiting area is close to staff who can provide care, support and observation. · Referral pathways to appropriate services are established, and all professionals working with the child/family are included. · Mechanical restraint is not used to prevent self-harm or the child leaving. · Policies and procedures are in place for children who leave before physical and mental health assessments and care are complete. · Policies and procedures are in place to identify children who frequently attend so that a multidisciplinary review can be arranged. |

· Appropriate safeguarding procedures. · Appropriate nursing observation policies. · The child’s care plan and safety plan if available. |

|

Ensure governance arrangements with emergency departments include: |

|

|

· Access to electronic record systems for mental services and medical treatments at the point of care where possible. · Jointly agreed referral pathways for physical and mental healthcare. · Jointly agreed approaches to initial assessment and triage. · Monitoring and documentation of the use of the Mental Health Act and Mental Health Capacity Act. |

|

Where hospital care is needed

Children who have been admitted to a paediatric ward following an episode of self-harm should have:

- An age-appropriate assessment by a mental health professional as soon as possible after arrival to complete a psychosocial assessment in line with the NICE Guidance on Self-harm assessment, management and preventing recurrence.

- A joint daily review by both the paediatric team and children and young people's mental health.

- Daily access to their family members or carers, if appropriate.

- Regular multidisciplinary meetings between the general paediatric team and mental health services.

Before discharge ensure that a discharge planning meeting is conducted to include:

- All appropriate agencies and people with arrangements for aftercare specified, including clear written communication with the primary care team.

- A plan for further management, drawn up with all appropriate agencies and people.

- Clarity around how best to support the child in their education setting. This should be shared with the School Designated Safeguarding Lead if consent to share has been obtained, or if the Crisis Team consider that there may be a risk to the child or others if the information is not shared.

Valuing mental health equally with physical health is a key priority in paediatric settings, and each acute trust should have a named Mental Health Champion who is a senior clinician.

Emerge Advocacy and east to west provide support for children who are in hospital because they’ve self-harmed, taken an overdose or are feeling suicidal. Staff and volunteers are specifically trained to support young people in Emergency Departments using a youth work approach and provide follow up care in the community after discharge. Emerge Advocacy operate within East Surrey Hospital, Epsom General Hospital, Frimley Park Hospital and Royal Surrey County Hospital. The east to west project operates within Ashford and St Peter’s Hospital.

Area self-harm pathways

Acute hospital trusts in Surrey should follow their internal trust pathway for self-harm and contact the Named Professionals within the trust for advice as required.

6. Information sharing and consent

Information sharing

Information sharing between professionals is essential to keeping children safe; no single person can have a full picture of a child’s needs and circumstances. Practitioners should be proactive in sharing information as early as possible.

Fears about sharing information must not be allowed to stand in the way of safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children. The Data Protection Act 2018 and UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) supports the sharing of relevant information for the purposes of keeping children safe.

Working Together to Safeguard Children 2023 states that

- All organisations should have arrangements in place that set out clearly the processes and the principles for sharing information. The arrangements should cover how information will be shared with their own organisation/agency and with others who may be involved in a child’s life.

- Practitioners should not assume that someone else will pass on information that they think may be critical to keep a child safe. If a practitioner has concerns about a child’s welfare or safety, then they should share the information with local authority children’s social care and/or the police.

- It is not necessary to seek consent to share information for the purposes of safeguarding and promoting the welfare of a child if there is a lawful basis to process any personal information required.

- Practitioners should aim to be as transparent as possible by telling families what information they are sharing and with whom, if it is safe to do so.

Health and social care staff should keep in mind that most children spend a large proportion of their time in school. It is in the best interest of the child for the staff supporting them to be informed about the best way to keep them safe and well.

Information Sharing: advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services for children, young people, parents and carers provides further advice on the legal framework and aims to:

- Instil confidence that the legal framework supports the sharing of information for the purposes of safeguarding

- Provide a straightforward guide on the core principles of timely and effective information sharing, that can be applied to day-to-day decision making

- Support organisations to develop processes, policies and training

Consent and transparency

Opening up about self-harm can feel daunting; being transparent around the follow up process and involving the child in decisions helps to build trust and a sense of safety.

The SHARE guide outlines best practice around consent, confidentiality and the sharing of information.

It is often the case that a particular characteristic and/or past action are preventing a child from giving their consent to share information. If a child perceives that confidentiality was inappropriately broken in the past, provide reassurance that information will only be shared in specific circumstances.

If consent to share information isn’t obtained:

- Use motivational interviewing techniques to explore why the child feels that way and explain why you need to share their information.

- Be clear around what information needs to be shared, with who, and for what purpose.

- Give the child control over how when their information will be shared e.g. letting the child chose the time / place / manner in which the information is shared.

- Explain that information sharing does not have to take the form of total disclosure, and some details (for example sexuality), can be kept private.

- Keep a record of what is / isn’t shared.

- Respect the child’s decision not to share if there are no safeguarding concerns and the child has capacity to make this decision.

7. Safety Planning

Safety Planning

As per the NICE guidance recommendations on self-harm assessment, management and preventing recurrence safety plans should be used to:

- establish the means of self-harm

- recognise the triggers and warning signs of increased distress, further self-harm or a suicidal crisis

- identify individualised coping strategies, including problem solving any factors that may act as a barrier

- identify social contacts and social settings as a means of distraction from suicidal thoughts or escalating crisis

- identify family members or friends to provide support and/or help resolve the crisis

- include contact details for the mental health service, including out‑of‑hours services and emergency contact details

- keep the environment safe by working collaboratively to remove or restrict lethal means of suicide.

The safety plan should be in an accessible format and:

- be developed collaboratively and compassionately between the child who has self-harmed and the professional involved in their care using shared decision making (see NICE guideline on shared decision making)

- be developed in collaboration with family and carers, as appropriate

- use a problem-solving approach

- be held by the child

- be shared with the family, carers and relevant professionals and practitioners as decided by the child

- be accessible to the child, family and the professionals and practitioners involved in their care at times of crisis.

All children who attend Emergency Departments in Surrey following an episode of self-harm are invited to create a ‘My Safety Plan’ with a member of the Crisis Team or Psychiatric Liaison Nurse. ‘My Safety Plan’ is designed to be a flexible, interactive document that can be adapted for any situation. ‘My Safety Plan’ can be used in any setting and you can download a template and watch a helpful video on how to use the safety plan on the Mindworks website.

Children are encouraged to share their safety plans with school. If the child gives consent, or if the Crisis Team consider that there may be a risk to the child or others, the plan is shared with the Designated Safeguarding Lead in their .

Remember, most children spend a large proportion of their time in school. It is in the best interest of the child for the staff supporting them to be informed about the best way to keep them safe and well.

Every effort should be made to seek consent in line with the advice above. If the child does not want their school to be involved, it is important to explore why the child does not want their school to know. Children’s right to confidentiality must be weighed up against the associated risk to themselves and others. The confidentiality of a child may be honoured in some cases of self-harm if it is deemed that they have the capacity to make that decision and the risks have not met the threshold for safeguarding. However, if a safeguarding threshold has been met then the right to consent is overruled and school would become part of the multiagency response within the discharge planning process. Children 12 years and under that fall outside of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 require those with parental responsibility to make the decision to share information if threshold for safeguarding has not been met.

In some cases of self-harm, Strategy Discussions and Section 47 Enquiries may be convened by Surrey Children’s Social Care and this process may replace the My Safety Plan process above.

Papyrus have also developed a safety plan that can be used for children who are experiencing suicidality. HOPELINE247 is a 24 hour support line that children and young people under 35, and adults supporting children and young people can call for support, including advice to create a Papyrus safety plan. Papyrus safety plans can be created confidentially online with a secure login, so that children and young people can revisit the plans as needed.

Responding to contagion (where a number of children are involved)

Social contagion is the spread of knowledge, behaviours and attitudes. If details of a self-harm method are shared this will increase the knowledge of them and increase the social contagion risk, putting more people at risk. Children and young people are more susceptible to social contagion.

If more than one young person in a setting has self-harmed, continue to provide support, separately, for those engaging with self-harm. Avoid raising the issue in a large group, but do ensure all young people are aware of where they can get help if they are struggling with difficult emotions.

In Surrey we advocate for a PSHE curriculum which strengthens well-being and promotes self-care and whilst we believe that there should be open conversations and topics should be addressed and self-harm may come up as a ‘touch point’ in some discussions, we don’t advocate specific lessons in PSHE around self-harm (see addressing self-harm in the curriculum). This is in line with the advice from the PSHE association.

Informing Public Health of a Social Contagion Risk

If you have identified a possible social contagion risk, please contact the Children and Young ’s Suicide Prevention Partnership by completing the CYP suicide emerging risks or social contagion form.

N.B. You must ensure you have sought advice from C-SPA and if required completed a referral form with parent/carer consent identifying details of children who are deemed to be risk.

Sharing this information supports Public Health in the Local Authority to map current issues presenting in Surrey, and helps to inform multi-agency action, including improvements and development of service provision. The intelligence shared is added to the Children and Young People’s Suicide Prevention Partnership database. It is then considered alongside intelligence from other Surrey schools and organisations, as well as national insights about children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Public Health will seek assurance that the school/organisation sharing intelligence is linked in with available support in Surrey, and if needs be, refer into respective partners for consideration of a multi-agency response meeting.

Further guidance for settings is available here: Identifying and responding to suicide clusters (publishing.service.gov.uk)

8. Impact on professionals

Impact on professionals

Supporting children and young people who self-harm is challenging and it is common to feel a range of emotions including sadness, shock, anger, fear, disgust, frustration and helplessness. You may find it difficult to empathise with a behaviour that is self-inflicted, you may feel a sense of compassion fatigue, or you may be reminded of friends and family members who are facing similar challenges. However you feel, try to be honest with yourself about your emotions and discuss them with your manager/supervisor.

When you are caring for others, you can find that you think a lot about their wellbeing and not about your own. The Five Ways to Wellbeing are a useful place to start caring for your own wellbeing. Consider how you might apply them to your work on a regular basis. Set small goals for yourself and build habits gradually.

The resources below can offer further support with your own physical and mental health:

For all:

- Mental wellbeing | Healthy Surrey lists a range of free and confidential services to support mental wellbeing, including local providers, talking therapies, crisis support and self-help information.

- Workforce wellbeing | Healthy Surrey contains a range of resources for employers and employees to support wellbeing at work.

- Designed for employers wishing to support the wellbeing of their workforce, Surrey County Council has published the How Are You? Framework as a tool to evaluate and improve wellbeing practices across Six Pillars of Wellbeing. If you wish to sign up, or learn more about ‘How Are You?’, email wellbeing@surreycc.gov.uk

- Use this template created by Mind, to have a conversation and develop a Wellbeing Action Plan with your manager.

- How Are You? is an online quiz which provides a personalised health score. They give advice on healthy weight, healthy eating, smoking cessation, physical activity, sleep and alcohol. How Are You? quiz - NHS (www.nhs.uk)

- Your Mind Plan is an online quiz which provides a personalised mental health action plan. Your mind plan (www.nhs.uk)

- Samaritans provide support 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Call 116 123 or visit Contact a Samaritan for other ways to speak with the

For Education Staff:

- Education Support helpline – call 08000 562 561 for free and confidential emotional support for teachers and education staff.

- The helpline is for any serving, former or retired member of staff who has worked in any part of the education sector including but not limited to Early Years, Primary, Secondary, Further, Higher, Adult and/or Prison education sector.

9. Online safety

Online safety for all

Report Remove (Childline) and Take It Down (ncmec.org)

Both services support children to confidentially report any sexual image or video of them that’s online and remove it from the Internet including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, OnlyFans and various pornographic sites. Take It Down is available in 28 languages and has a reassuring step-by-step explanation of the process.

Advice for families on how to stay safe online including how to talk with your child about online safety and how to set parental controls.

The Internet, Relationships & You (thinkuknow)

Support for children around issues they may be facing online e.g. harassment, relationships, pressure to send nudes

Adaptable resources designed to equip educators and parents and carers, to support young people aged 11 and over with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). Topics include healthy relationships, digital wellbeing and online pornography

Online safety for teachers and home educators

Teaching activities to start empathetic, honest, and evidence-based conversations on online hate and how to tackle it with 13-17 year olds.

This guidance outlines how to help pupils understand how to stay safe and behave online as part of existing curriculum requirements.

Surrey Healthy Schools Self-Evaluation Tool

All Surrey primary and secondary (including independent and specialist schools) can freely access the Surrey Healthy Schools Self-Evaluation Tool in order to support the development of effective and holistic provision and practice.

10. Appendix A

Supporting a child who has self-harmed: a guide for professionals that work in non-healthcare settings in Surrey

Appendix A - printable version

11. Appendix B

Appendix B: Crisis lines and safeguarding: Surrey and North-East Hampshire Mental Health Patient Referral Pathway for professionals

Appendix B - Printable version - Crisis lines and safeguarding

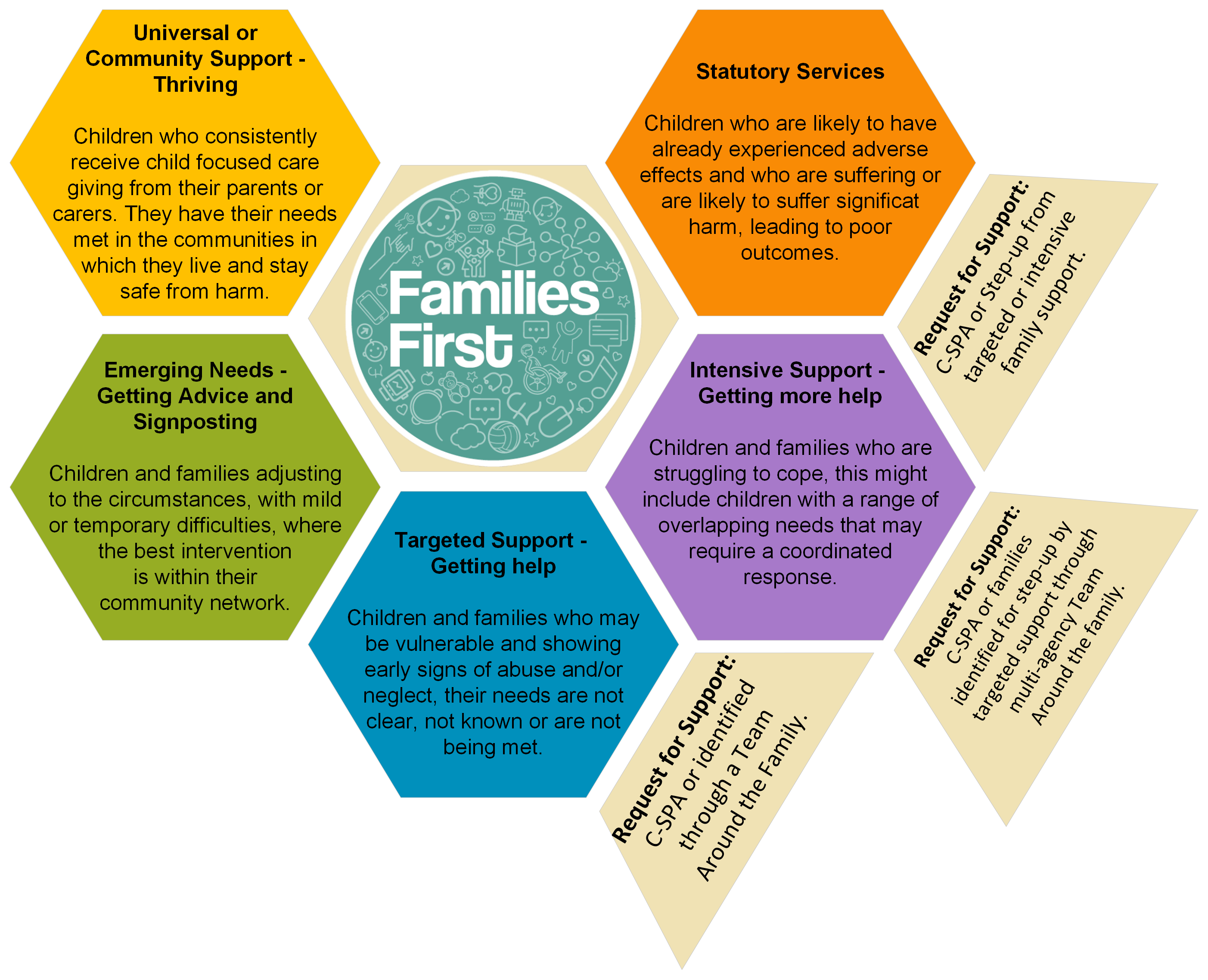

Accessing services on the Continuum of Support for children and families living in Surrey

The Surrey Children’s Single Point of Access (C-SPA) is the umbrella term for the front door to support, information and advice for residents, families and those who work with Surrey Children. This replaces the Surrey Multi Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH). The C-SPA facilitates access to services on the Continuum of Support for children and families living in Surrey , it also provides direct information, advice and guidance about where and how to find the appropriate support for families. The Continuum of Support indicators can be used alongside the Continuum of Support guidance to assist decision making and determine the appropriate referral pathway.

Phone: 0300 470 9100 (Monday – Friday 9am – 5pm)

Out of hours phone: 01483 517898 to speak to our emergency duty team.

Email: cspa@surreycc.gov.uk

Please complete a Request for Support form (this replaces the Multi-agency referral form (MARF). When a notification is received via the Request for Support Form, the process outlined below is followed.

The referral should include information about the background history and family circumstances, the community context and the specific concerns about the current circumstances, if available.

C-SPA Child Protection Consultation Line

The Child Protection Consultation Line provides advice and support to professionals to ensure we are able to direct you to the most appropriate service that can meet the child and family’s needs. The Consultation Line is open to all professionals who work with families who live in Surrey.

Availability: 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday

Phone: 0300 470 9100 option 3

Click here for further information – SCC – Report a concern about a child or young person

School Nurse Drop-In Service

Most secondary schools facilitate a school nurse ‘Drop In’ service. The Drop-In service provides an opportunity for the school nurse to contact students who may have self-referred or been referred by school staff, other professionals or family/carers. The majority of children present with emotional wellbeing issues, which may include self-harming behaviours

Telephone: The Chat Health text number is: 07507 329 951 The Advice Line is: 01883 340 922

Website: https://www.childrenshealthsurrey.nhs.uk/.../school-nursing-general

Every school can access their school nurse through their local 0-19 team. If schools are unclear of who their school nurse is, they can contact the 0-19 advice line on 01883 340922 who will provide contac.

12. Appendix C

Resources for Children and Families

Please use the links below to signpost children and families to sources of support.

|

For Children and Young People

Mindworks The Mindworks website lists mental health and wellbeing resources including telephone and in-person support Mental Health and wellbeing support :: Mindworks Surrey (mindworks-surrey.org)

The website includes a range of self-help ideas: Looking after yourself: self-care :: Mindworks Surrey (mindworks-surrey.org)

Chat Health Chat Health is a text service for anyone aged 11-10 to reach out to a school nurse for help with a range of issues. You can also text to make an appointment with one of our school nurses confidentially.

The service is for anyone aged 11-19 at secondary school looking for confidential advice on a wide range of issues such as bullying, emotional health and wellbeing, sexual health as well as illnesses. The service is available Surrey-wide. Chat Health operates Monday to Friday 9am – 5.00pm (excluding bank holidays). The Chat Health text number is: 07507 329951.

Crisis Support If you are worried about yourself, please call our 24/7 mental health crisis line free on 08009154644 to talk with a trained call handler who will provide advice, support and signposting to a range of community services. It’s open all day and all night, seven days a . |

For parents/carers

Healthy Surrey A range of self-help, support and advice resources for children and young people and their parents and carers

Mindworks The mental health support service for children and young people in Surrey. The website has a range of different support resources Home :: Mindworks Surrey (mindworks-surrey.org) and a specific parent/carer support area: Parent Support :: Mindworks Surrey (mindworks-surrey.org)

CYP Mental Health Crisis Line If you are worried about your child, please call our 24/7 mental health crisis line free on 0800 915 4644 to talk with a trained call handler who will provide advice, support and signposting to a range of community services. It’s open all day and all night, seven days a week. The crisis line is available for children and young people from the age of six. You can use the number whether or not you are already receiving mental health services. No formal request for support is needed. Family Voice Surrey Family Voice Surrey gives parents a strong collective voice, a forum to share knowledge and empowerment to improve opportunities for children.

|